13/08/2024

The Art of Writing: A Set of Reviews

The best thing you can do to improve your writing is practice, but an expert's guidance can make that process significantly faster. Plenty of people have written books with the aim of providing that guidance, but which ones should you read? Today I’ll be reviewing some of the books off my shelf that deal primarily with the creative side of writing, the art of turning words on a page into a narrative that will hook readers from the first page to the last. Knowing how to string sentences together is important, but they serve no purpose unless you give them one.

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

By Stephen King

Pages: 351

Published: 2000

Spoooooooky

We start with the lengthiest of the three books we’ll be covering, Stephen King’s On Writing. The first thing King states in the first of three forewords is that this book exists so he can talk about the language, which he does. The second foreword posits that he will keep the book short to avoid bullshit, and vows to follow Strunk’s maxim, “Omit needless words.” With the book being twice the length of most others, his success there is open to debate.

The first section (roughly a third of the book) is biographical, an attempt to explain what made him the writer he is today. Entertaining as this highlight reel is, it may not be incredibly useful to anyone who isn’t interested in studying or emulating King. It’s also a somewhat outdated journey, many of the avenues King travelled simply do not exist anymore, namely the many print magazines where he got his start. It is fun to read though, and I personally appreciate it as a sort of inspirational tale. If a nobody, working multiple jobs that should have killed him, in the middle of poverty ridden rural America, can find the time to master the art of writing, what’s stopping me?

At the end of this we get our first piece of actual advice, delivered via an elongated metaphor, which is to take writing seriously. Not necessarily to be serious, but to treat the undertaking with the seriousness it deserves, to put your whole self into it. So far so good.

Next up is some basic advice on the avoidance of purple prose, adverbs, passive voice, etc. At this point I’m starting to wish he could be a little more concise, after the no-nonsense approach of Strunk & White this rambles far too much for my liking. He touches on a few more basic things and then we get to the contentious parts.

First is his sweeping declaration that only a chosen few may become truly great writers, with Shakespeare, Faulkner, and Yeates among his examples. If you weren’t born with this innate talent bestowed upon you by the universe you’ll never be on this level. In his view the competent may become good, but the good cannot become great, nor can the bad become competent. I will now assert my own declaration, which is that he’s full of bullshit.

As with all things, natural talent helps immensely, I won’t argue that. However the vastly more important element is the effort you put in. Your natural talent for crafting narrative doesn’t mean anything unless you bother to sit down and put it to work, and that talent will eventually be outstripped by anyone who dedicates themselves to mastering their craft. So no, I don’t believe inherent talent determines where you end up, with enough time to learn and grow any of us can be Shakespeare.

King’s next contentious opinion is about television, and it’s at this point that it becomes blindingly obvious how old and crotchety this man is. In his defence I can understand how someone growing up with early television could conclude that it isn’t worth bothering with. If all I had to watch was game shows, sitcoms, and Ronald Reagan shilling for General Electric, I’d come to the same conclusion. Times have changed though, we now have creators who’ve learned to use the medium to do things that can’t be done anywhere else, and writers producing stories that rival books. The Same Sky is a good example, as is Hungry Ghosts. Both are mini-series, taking full advantage of their medium to tell engaging and thought provoking stories that just would not hit the same in any other format. A movie would truncate the story, a book couldn’t convey the pauses quite right. To completely write off the medium as a loss is short-sighted, and bizarre when you’re still willing to watch baseball on tv, as King says he loves to do.

And now we arrive at the hill I shall die on, the pantsing versus plotting argument. To the unaware, plotting refers to writing with an outline, with a plan and notes to keep you on track. Pantsing, conversely, is when you do none of that, and instead set the characters and the story loose, while you dutifully follow along behind recording what happens. There are pros and cons to each, pantsers generally never have issues with characters behaving wrong to suit the story, while plotters put out a generally tighter product, with little to no meandering down unnecessary detours. Stephen King doesn’t use the term, but he’s a pantser, dutifully recording his stories as they are revealed to him. He also asserts that plotting ruins story, which as someone who plots, I take great offence to.

I again must disclaim, he has a point, plotting can ruin a story. The disastrous final season of Game of Thrones can be partially attributed to the showrunners abandoning the pantsing approach Martin employs, the approach that created such compelling characters and the chaos of their many unpredictable deaths, to instead plot their way towards a predetermined conclusion. The result was people behaving wildly out of character because they were no longer following their own motivations, but instead the demands of the plot.

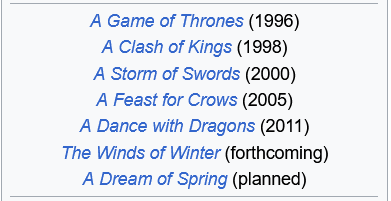

A Song of Ice and Fire, the book series that inspired the show, also illustrates the issues with pure pantsing. Martin has pantsed his way through five enormous novels, thousands of pages in a single continuity, letting it develop as it will the whole way. The result is that the whole thing has grown monstrously complex, and requires more and more time to write with each book.

The release schedule of the series as it stands.

Two years between installments, a very reasonable time for books of this length, became five, and then six. At the time of writing this we are just shy of thirteen years since the last book. While it’s not definitive, this does appear to suggest that pantsing has its limits.

Plotting isn’t perfect either, which is why in my own writing I tend to mix the two. I like to start by examining my characters and their motivations, writing a skeletal outline version of the story, and then proceed to writing the fully fleshed version. During that final version though I find it is important to be open to change, to be ready to alter details to better suit the more comprehensive understanding you develop as you write the story. Planning is good, and I recommend it, but you should never let it strangle your story.

All that said, is this book worth it? The answer is, it depends. If you’re a pantser already you’ll love this approach to writing, if you’re a plotter not so much. Ignoring that, there are other things to pick at, like taking too damn long to get to the point, being harshly prescriptive and overly crotchety, and of course that a third of the book is a biography. Otherwise there is some good advice, even if some of it is so basic that most writers probably already know it.

5/10 - Average

How To Write Damn Good Fiction

By James N. Frey

Pages: 149

Published: 1994

Also published as "How to Write a Damn Good Novel II: Advanced Techniques for Dramatic Storytelling". I prefer the brevity of my copy.

Now we move on to a significantly quicker read, James N. Frey’s How To Write Damn Good Fiction. This book is interesting in that it isn’t aiming to start at the start like most books do, instead it positions itself as an advanced course for those that already know the basics. It’s a direct sequel to How To Write A Damn Good Novel, but it’s not necessary to have read the first book (I haven’t) to understand the second. Also of note is that in this book he overrides some of his previous advice, throwing out “pseudo-rules” he no longer agrees with.

Frey’s opinions on pseudo-rules, as explained during the introduction, form an interesting foundation for this book. In Frey’s words: “Pseudo-rules are taught to beginners to make life easier for the creative-writing teacher.” These are rules like “You can’t change viewpoint within the scene,” or “The author must remain invisible.”

These rules help rein in some of the most debilitating problems commonly experienced by beginner writers, allowing them to seem more in control of themselves and their text than they actually are. For the more experienced writer however, who no longer needs training wheels to keep them from toppling over, these rules restrict their ability to develop. Any writer who has learned these pseudo-rules as a beginner will have to unlearn them later, better to skip right past them, says Frey.

Now that we have a firm understanding of his philosophy, let’s dig into the book proper. There are nine chapters to this guide, and I’ll be summarising the most interesting bits for you.

We start with the Fictive Dream, the essential flow state that all good novels will trigger in their readers. It’s a solid and straightforward chapter covering how you create and then wield sympathy, empathy, and identification to fully transport a reader into your world.

Next chapter contains my favourite piece of advice, hooking the readers immediately with a burning story question. This means raising a question that instils curiosity (or even better, anxiety) in your readers within the first three sentences, not paragraphs as some claim. I consider this to be the best piece of advice the book has to offer, and probably the single most effective change you can make to your writing if you’re struggling to get people to even pick it up.

Next is a look at how to write characters, with the main focus being on making them dynamic, memorable, and overall someone worth knowing. After that we spend two chapters on premise, first on how to create one and then how to use it. These are all solid, nothing crazy here. The chapter on voice is quite refreshing, encouraging you to have more rather than less, and disposing of the adage that certain narrative perspectives (eg. first person versus third) have inherent limitations.

One excellent chapter that could save a lot of new writers is the importance of not breaking the contract you have with the reader. If you’ve promised a mystery novel where the protagonist will solve the murder, the protagonist needs to solve the murder, they can’t just be tagging along as others do the important work like in A Murderous Yarn. The advice in this chapter is good, except for the suggestion you join the RWA. Never join the RWA.

Lastly we have “The Seven Deadly Mistakes”, a sort of miscellaneous grab bag chapter, a chapter on the importance of writing with passion. The seven mistakes serve as a useful sort of tl;dr with its rapid fire selection of topics, while passion ties in closely to the first of the seven deadly mistakes: Timidity. It’s an inspiring note to end on, the importance of committing wholeheartedly to whatever you choose to do. The Room wouldn’t be the legend it is if Tommy Wiseau hadn’t believed fully in its creation, it would just be a forgettably bad movie. Passion is the guiding light of all writers, and the thing that makes our work last.

If you feel you’re ready to leap into the deep end with your writing, this is a good book to pick up, even if the assessment of the “current state” of the industry is hysterically outdated.

7/10 - Would Recommend

Scene & Structure

By Jack M. Bickham

Pages: 163

Published: 1993

There’s a version with a pretty blue cover, but mine is white.

You can’t accuse this book of wasting time. It has no introduction, just leaping straight into the first chapter, and it never wastes any of the words in its brief duration. If you subtract the various appendices (mostly novel excerpts presented as case studies), this is the shortest of today’s books at only 130 pages.

Despite these points it is the book I personally find the hardest to stick with. It lacks the abundant colour and flavour of King or Frey, and combined with its laser focus on how to structure a story, it comes across very dry and technical.

This shouldn’t be enough to sink it if those technical lessons are solid however, which they are. As mentioned the focus of this book is squarely on making sure the structure of your book is rock solid, built to a framework laid out in detail over the course of the book.

We have to note upfront the “classic” structure of a novel that Bickham argues is the starting point for all structural sound and commercially successful novels, which is as follows:

Scene → Sequel → Scene → Sequel

In this context a scene is defined as a segment where things happen externally, “onstage” as it were. The audience can watch the dialogue and action play out in front of them. A sequel in this context happens internally, the characters inner thoughts and workings, revealed to the audience only because they are written out for them. In Bickhamn’s model, every external scene is linked to another by an internal sequel that explains, justifies, and clarifies the events of the plot and goals of the characters.

Of course once this formula is introduced, we spend a lot of time discussing the myriad exceptions to the rule, but always remembering to start with the formula, and mix things up after.

Heavy emphasis is placed throughout the book on the importance of cause and effect, of stimulus and response. For every event that transpires, there should be a reaction that logically follows. Zoom out to a wider structural view and you can see the whole story as a series of events creating reactions leading to new events to new reactions and so on until you have a full length novel. Bickham is correct in that if you follow this sequence, you’ll never have a problem with characters or events being illogical.

Chapter two provides an excellent piece of advice on how to start and end your story: Start with a story question, end by answering that question. With this maxim in hand you can then answer all your burning questions about length, where to start and end, whether a subplot should be there, etc. It’s a pretty good rule to keep in mind when laying out the skeleton of a story, guaranteed to keep you at least mostly on the right path, probably my single favourite takeaway.

It also offers plenty to think about when trying to finetune the pacing of your novel, whether that means speeding it up or slowing it down, as well as some great advice on using chapters to heighten tension.

Like Bickham’s formula for novel writing, this is a solid book that can be counted upon to deliver what was promised. Everything logically follows upon from what came before, there are no bullshit twists from nowhere. My main detraction is that it is quite dry and difficult to read through, maintaining focus on it for extended periods is challenging.

I haven’t tried to implement the entirety of Bickham’s formula, so I cannot attest to its effectiveness, but I see no reason to doubt him. He did publish more than 70 books in his life, he must have been onto something. It’s not the most exciting read, and those who are opposed to heavy plotting will blanch at its strict formulas, but it's worth taking a look at.

6/10 - Would Recommend